Web-based Finnish Sign Language Vocabulary Test

Web-based Finnish Sign Language Vocabulary Test (FinSL-VT; Kanto, Syrjälä & Mann, 2021) is an adaptation of the British Sign Language Vocabulary Test (BSL-VT; Mann, 2009; Mann & Marshall, 2012) to assess FinSL vocabulary knowledge of children acquiring FinSL. More specifically the test measures the degree of strength of the mappings between form and meaning for items in the core lexicon (Mann & Marshall, 2012, p. 1031). The web-based BSL vocabulary test by Mann (2009) was adapted for FinSL following the steps outlined by Enns and Herman (2011) and Mann, Roy and Morgan (2016). The test was piloted with 24 hearing and deaf children acquiring FinSL between the ages 4;1 to 15;7 years (see more detailed description of the adaptation process in Kanto, et al., 2021). After the pilot phase, larger survey data was collected and vocabulary knowledge was evaluated from altogether 140 hearing and deaf children acquiring FinSL at the ages between 4;1 to 15;7 years (Kanto, in progress). Currently, FinSL-VT is part of larger web-based assessment tool https://viittomatesti.cc.jyu.fi/ that includes altogeter five different adapted assessment instruments that can be used to evaluate different aspects of children’s FinSL skills, such as vocabulary, grammatical and narrative skills, between the ages 0;8 to 15;11 years.

Development of the instrument

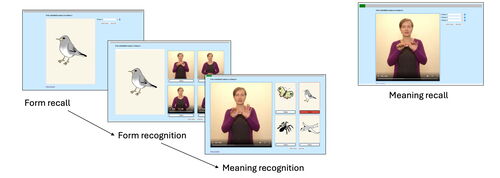

Like BSL-VT and its adaptation ASL-VT (Mann et al., 2016), also FinSL-VT consists of four ditterent tasks that measures different aspects of vocabulary knowledge. Two of the four tasks (see Figure 1), “meaning recognition” and “form recognition,” assess vocabulary comprehension. In the “meaning recognition” task, child sees a sign on the computer screen and selects the image that best illustrates the meaning of the sign. In the “form recognition” task, child sees an image and four signs and is asked to select the sign that best matches the image. The remaining two tasks, “form recall” and “meaning recall,” assess vocabulary production. In the “form recall” task, child sees an image and are asked to produce the corresponding sign. Finally, for the “meaning recall” task, child sees the target sign presented on the screen and is asked to supply three different signs with an associated meaning. Figure 1 also illustrates the construct of strength of form-meaning mapping, ranging from weak to strong understanding of form meaning mapping.

Figure 1. FinSL-VT tasks.

The FinSL test is targeted for children acquiring FinSL at the age between 4 to 15 years. After the pilot phase, the 120 items were divided into two parallel parts, and then versions FinSL-VT A and B of the test were implemented, each with a total of 60 items. When examining an individual child's vocabular skills, parallel versions are used alternately in successive assessment sessions. This is to avoid the child remembering the items in the material. Additionally, three of the four different tasks were made as computer adapted format (see Figure 2). This means that the assessment of the child’s FinSL vocabulary skills starts with the form recall task. The items for which the child did not know the correct answer move on to the next tast, which is form recognition task. Again, in this form recognition task, the items for which the chid did not find the correct answer move on to the next task, which is the meaning recognition task. In this way, after the correct answers of specific items, the number of items in different tasks decrease gradually. However, meaning recall task always includes all the 60 items.

Figure 2. FinSL-VT tasks order in computer adapted format.

Instructions on how to administer the test are provided in printable test manual at the website of FinSL assessment tool. The manual also contains detailed information on scoring. The test administer marks the scoring in the two recall tasks while administrating the test with the child. In the two recognition tasks the web site scores child’s answers automatically. After each test is completed the website provides the scores, number of correct and incorrect answers automatically for the test administer. Additionally, FinSL web-based assessment tool provides a follow-up data on the child's performance at different points in time when the child’s has condcted the test more than once.

Strength and weaknesses

The multilayered approach of FinSL-VT (as well as it’s earlier versions BSL-VT and ASL-VT) enables a more in-depth evaluation of vocabulary knowledge, as the test evaluates both quantitative and qualitative aspects of vocabulary knowledge, that is, vocabulary size and strength as well as both productive and reseptive skills. This makes it a particularly valuable tool to assess children from linguistic minority backgrounds, including deaf children, who tend to perform low on standardized language assessments (Hadley & Dickinson, 2020). Additionally computer adapted format makes it faster to complete all the four tasks when child’s vocabulary skills are assessed and for this reason the test is more manageable for child, teacher and practitioner to conduct and administer.

However, no norms are avaliabe for the test yet.

Psychometric information (in Kanto, Syrjälä & Mann, 2021, pp 154-155)

- Reliability

Internal consistency

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and corrected item-total correlations. Cronbach’s alpha for all tasks together was 0.717 and corrected item-total correlations ranged from 0.790 to 0.862. The meaning recall task indicated the lowest corrected itemtotal correlation (0.790), and a high Cronbach’s alpha for any item deleted (0.960) compared with other tasks. For this reason, Cronbach’s alpha was measured again but this time separately for each task. The average alphas of three tasks, namely meaning recognition (0.800), form recognition (0.790), and form recall (0.790) met the requirements of coefficient, whereas the significance for the meaning recall task was low (0.500).

Item analysis

An item analysis was run to identify any items that had been answered correctly or incorrectly by all participants and should be removed for this reason. All participants correctly answered seven items on three of the four tasks (meaning recognition, form recognition, and form recall) but none of these items were passed by all participants in the meaning recall task. Additionally, no item was failed by all participants within one task. Thus, no item needed to be removed.

Inter-rater reliability (Cohen's kappa)

Inter-rater reliability was evaluated for the two production tasks; form recall and meaning recall tasks. Whereas, items from the two recognition tasks were automatically scored by the computer upon selection of the responses via mouse click.

Resultse showed:

- Agreements between raters’ judgments for scoring the form recall task (k=.89)

- Agreements between raters’ judgments for scoring the meaning recall task (k=.81)

Validity

Content validity

Content validity of test materials was ensured in three different steps:

- by working closely with the deaf/hearing expert panel during the whole adaptation process,

- by collecting Mode of Acquisition (MoA, Wauters et al., 2008) ratings from teachers of deaf children (see stage 5 of the adaptation process). MoA ratings of target items reflects the range/spread of item types from concrete to abstract signs: spread of ratings over most of the range (1-5) except ‘5’ (signs that are acquired exclusively through language)

- by involving seven students of the Master Program of Sign Language at the University of Jyväskylä to validate the target pictures.

All these stages were important in ensuring the content validity of the FinSL-VT even more so because of the larger number of test items and distractor items that had to be revised compared with the adaptation process between the BSL-VT and ASL-VT (see stage 2) (Mann et al. 2016).

The validation of target items was done in two stages: one focusing on target signs and one with focus on target pictures. Target signs were validated based on teacher ratings of the type of knowledge necessary for acquiring each target sign (“MoA”), an approach that was also used by Mann et al. (2016), based on the work done by Wauters et al. (2008). The Likert-type scales that teachers used ranged from “1” (perceptual associations/learning the meaning through experiences) to “5” (linguistic associations/learning the meaning through language). Similar to the study by Mann and colleagues (2016), four Finnish teachers of the deaf (two deaf and two hearing) made use of the full range of ratings suggesting that the item pool for the FinSL-VT was appropriate. MoA ratings showed an average score of 3.3 (1=12%, 2=8%, 3=23%, 4=25%, 5=23%). Overall, the Finnish teachers gave slightly higher ratings compared with the results of Mann et al. (2016), which could be due to the considerable number of signs that had been replaced as part of the adaptation. In order to validate the target pictures for the FinSL-VT, deaf (N=4) and hearing (N=3) students from the Master Program of Sign Language at the University of Jyväskylä were presented with pictures of all target items and asked to write down for each their three best guesses what it meant. In those cases where 50% or more of the students did not guess the correct answer, the picture (not the item) was replaced. This happened in 10 cases (out of 120).

Construct validity

Construct validity was evaluated by examining whether participants’ performance on the four tasks correlated with age. Additionally, the differences between participants’ performance across the four different FinSL tasks were investigated. This was done to test whether the observed hierarchy of task difficulty would meet our predictions based on the underlying model of strength of form-meaning mapping.

First, we carried out bivariate correlations between each of the tasks and age, using a Pearson correlation coefficient, with the alpha level reduced to 0.013 to compensate for multiple (k=4) comparisons. Findings revealed strong, positive correlations, which were statistically significant between

- age and meaning recognition; R(24)=0.798, p<0.01;

- age and form recognition, R(24)=0.774, p<0.01;

- age and form recall, R(24)=0.777, p<0.01;

- age and meaning recall, R(24)=0.764, p<0.01.

Next, we carried out partial correlations between the different tasks, controlling for age, with the alpha level reduced to 0.008 for multiple (k=6) comparison. Performances on all tasks remained significantly correlated:

- meaning recognition and form recognition, R(21)=0.860, p<0.001,

- meaning recognition and form recall, R(21)=0.645, p<0.001,

- form recognition, and form recall, R(21)=0.668, p<0.001,

- form recall and meaning recall, R(21)=0.476, p<0.05.

Upon running all correlations a second time, using bootstrapped confidence intervals to account for the small sample size, no differences were found.

A series of paired sample t-tests was carried out to compare performance across the four tasks (alpha level reduced to 0.008 to compensate for multiple (k=6) comparisons). Performance between all tasks was significantly different (p<0.01). Post hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections were carried out to compare performance across the four tasks

(alpha level reduced to 0.008 to compensate for multiple (k=6) comparisons). Results showed that

- participants scored higher on meaning recognition than form recognition (p<0.000);

- higher on meaning recognition than form recall (p<0.000);

- higher on meaning recognition than meaning recall (p<0.000);

- higher on form recognition than form recall (p<0.002);

- higher on form recognition than meaning recall (p<0.000),

- higher on form recall than meaning recall (p<0.000).

Concurrent validity was examined by comparing children’s performance on the four tasks in FinSL-VT with their Finnish Sign Language Reseptice Skills Test (FinSL-RST) scores. Bivariate correlations between each of the vocabulary tasks and performance on the FinSL-RST showed strong, positive correlations with

- the meaning recognition task, R(15)=0.658, p<0.01;

- form recognition task, R(15)=0.755, p<0.01;

- form recall task, R(15)=0.743, p<0.01

No significant correlations were found with the meaning recall task. When carrying out partial correlations between the different tasks in FinSL-VT with FinSL-RST and controlling for age, the following correlations remained significant:

- FinSL-RST and form recognition task, R(15)=0.666, p<0.0,

- FinSL-RST and form recall task, R(12)=0.645, p<0.05.

No significant correlations were found with meaning recognition and meaning recall tasks.

As an additional validation mechanism, the two comprehension tasks (form recognition, meaning recognition) were presented to a control group of 24 age-matched hearing children (M: 10;0 years SD: 3.3 years, range 4;10–15;11 years; 18 females) with no previous knowledge of FinSL. The percentage of correct responses on the meaning recognition task was 37% (SD: 9.1, range: 30–61) and on form recognition 36% (SD: 9.0, range: 27–63). The results for both tasks are above chance level (25%). One possible reason for this is that the signer mouthed the Finnish word for some signs, and the hearing children were able to read their lips. Another reason may be the iconicity (resemblance to action, movements, location, and shapes of object and/or person) of some signs, which may have aided nonsigners in selecting the correct response. This has been discussed in previous studies, for example, by Hermans et al. (2010).

Availability

The FinSL-VT is available through https://viittomatesti.cc.jyu.fi/ without any charges. Please contact the correspondent author laura.kanto@jyu.fi for more detailed information.